In elementary school they tried to make us all memorize Robert Frost — either “Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening” or (for our sins) “The Road Not Taken” — was it the same in your school? I gather that in Britain, “Adlestrop” is the equivalent. But in the United States, the poem people actually know best is “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” a.k.a. “The Night Before Christmas.” It’s kind of nice that they try to enforce certain kinds of literature, but people keep on loving what they love. All together now:

In elementary school they tried to make us all memorize Robert Frost — either “Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening” or (for our sins) “The Road Not Taken” — was it the same in your school? I gather that in Britain, “Adlestrop” is the equivalent. But in the United States, the poem people actually know best is “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” a.k.a. “The Night Before Christmas.” It’s kind of nice that they try to enforce certain kinds of literature, but people keep on loving what they love. All together now:

’Twas the night before Christmas, and all through the house

Not a………..

You got it, right?

But even though people can repeat whole swathes of the poem, we have imposed so much of modern Christmas on the text that it’s easy to miss the surprising information it reveals about the St. Nicholas of nineteenth-century America — the St. Nicholas envisioned by the poem. I’m just going to state this outright:

St. Nicholas — Santa Claus, as we usually call him today — is miniature. By this I mean that he is tiny. Let me repeat that: St. Nicholas is miniature. He’s not human-sized. He’s diminutive; he’s eensy-weensy. This is so freaky to get one’s head around that I am going to repeat it: ST. NICHOLAS IS A TINY MINIATURE BEING.

Let’s look at the poem:

When what to my wondering eyes did appear,

But a miniature sleigh and eight tiny rein-deer,

With a little old driver so lively and quick,

I knew in a moment he must be St. Nick…

His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow…

He had a broad face and a little round belly

That shook when he laughed, like a bowl full of jelly.

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf…

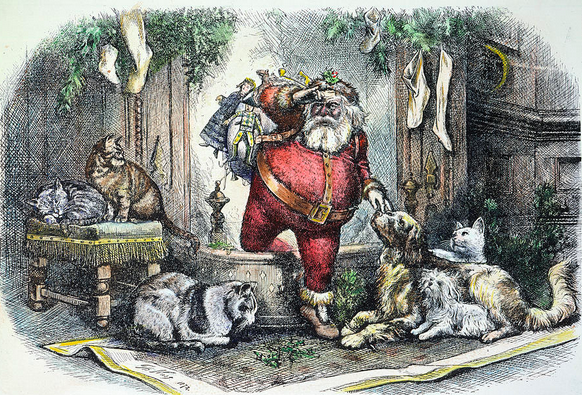

Nineteenth-century painting of St. Nicholas and the tiny reindeer — note his size in comparison to the chimney.

This small size explains how St. Nick is able to get up and down through the chimney. More importantly, this illustrates a perennial trend in the human interpretation of supernatural or magical beings. When they live apart from humans, like the Olympian gods or the Old Norse gods, these beings tend to be larger than life. Trolls, giants, and huge monsters like Grendel, who eats men for dinner after tucking them inside his glove — all these supersized beings live out in the wilderness. But when the magical beings move closer to human habitations, they tend to become miniaturized. Thus we get British pixies, fairies, sprites, brownies, and hobgoblins, German kobolds, Swedish tomtes, and a host of other folk, some good and helpful, some mischievous, some malevolent, but all smaller than humans. They tend to live in farmyards and around human dwellings. They interact with humans, helping the good and punishing the bad. The householders leave gifts for them such as bowls of milk. They frequent our dwelling places, but they’re rarely glimpsed. You can even see the themes of smallness and domesticity operating in the case of hobbits:

“I suppose hobbits need some description nowadays, since they have become rare and shy of the Big People, as they call us. They are (or were) a little people, about half our height, and smaller than the bearded Dwarves….There is little or no magic about them, except the ordinary everyday sort which helps them to disappear quietly and quickly when large stupid folk like you and me come blundering along, making a noise like elephants which they can hear a mile off.” (The Hobbit, chapter 1)

St. Nicholas was understood as miniature throughout most of the nineteenth century, as illustrations make clear. Obviously this required him to be miniaturized, as he began as a third-century bishop of Myra, and bishops are generally human-sized. He was magical before he was miniature: he became known as a present-giver in a miracle in which three unwed daughters had no dowry, and hence were going to be doomed to a life of sordid money-earning, if you catch my drift. But St. Nicholas passed by their window and slipped gold into stockings which were hung before the fire to dry. It wasn’t so much a matter of rewarding good behavior as preventing the bad, which a stocking full of gold did very effectively.

A digression on stockings and mantels: I never quite understood why the stockings were hanging on the mantel until I lived in Britain, where dryers are rarer than they are in the U.S., and I tried to dry socks in a damp climate — when you live in a house without central heating, the only way to get stockings dry is to hang them by the fire. Those penurious daughters merely hated damp feet. They weren’t hanging their stockings on the mantel, though, since fireplaces in side walls, the kind of fireplace with a mantel, weren’t invented until the late Middle Ages. The three girls would have lived in a house with a central hearth, in the middle of the floor, with a hole in the ceiling above it. However did they hang their stockings up? History does not relate. And could supernatural beings descend carefully through that central smokehole in the roof, or would they just plummet into the house? This must be why St. Nicholas just decided to throw the money in through the window.

A late medieval fireplace and mantel, sans stockings, of the type unknown at the time of the real St. Nicholas, bishop of Myra.

But anyway, in the development of the legend of St. Nicholas, Clement Clarke Moore’s poem was a turning point. When Moore first published “A Visit from St. Nicholas” in the Troy, New York Sentinel, in 1823, St. Nicholas was known primarily as a legendary figure whom the Dutch had imported; indeed, the first Dutch ship to travel to the New World, the Goede Vrouw, in 1621, had St. Nicholas as its figurehead.

In 1806 Washington Irving described the legends of St. Nick as they appeared among the Dutch in New Amsterdam (later to be renamed New York):

“…in the sylvan days of New Amsterdam, the good St. Nicholas would often make his appearance in his beloved city of a holiday afternoon, riding jollily among the tree tops or over the roofs of the houses, now and then drawing forth magnificent presents from his breeches pockets and dropping them down the chimneys of his favorites. Whereas, in these degenerate days of iron and brass he never shows us the light of his countenance nor ever visits us, save one night in the year; when he rattles down the chimneys of the descendants of the patriarchs, confining his presents merely to the children in token of the degeneracy of the parents.”

From this description it’s not clear what St. Nicholas is riding, but in a later description Irving mentions that he has a wagon (spelled waggon). Irving concocts a vision of the founding of New Amsterdam, dreamed by a character named Olaffe Van Kortlandt:

“And the sage Olaffe dreamed a dream – and lo, the good St. Nicholas came riding over the tops of the trees in that self same waggon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children; and he came and descended hard by where the heroes of Communipaw had made their late repast. And the shrewd Van Kortlandt knew him by his broad hat, his long pipe, and the resemblance which he bore to the bow of the Goede Vrouw. And he lit his pipe by the fire, and sat himself down and smoked; and as he smoked, the smoke from his pipe ascended into the air, and spread like a cloud over head. And the sage Olaffe bethought him, and he hastened and climbed up to the top of one of the tallest trees, and saw that the smoke spread over a great extent of country – and as he considered it more attentively, he fancied that the great volume of smoke assumed a variety of marvellous forms, where in dim obscurity he saw shadowed out palaces and domes and lofty spires, all which lasted but a moment and then faded away, until the whole rolled off, and nothing but the green woods were left. And when St. Nicholas had smoked his pipe, he twisted it in his hatband, and laying his finger beside his nose, gave the astonished Van Kortlandt a very significant look; then mounting his waggon, he returned over the tree tops and disappeared.

“And Van Kortlandt awoke from his sleep greatly instructed, and he aroused his companions, and related to them his dream; and interpreted it, that it was the will of St Nicholas that they should settle down and build the city here: and that the smoke of the pipe was a type how vast should be the extent of the city; inasmuch as the volumes of its smoke should spread over a wide extent of country.”

This origin-story of New Amsterdam faded from legend, but the phrase “laying his finger beside his nose” has seized the attention of scholars, who are naturally reminded of the lines from “The Night Before Christmas”:

…He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work,

And filled all the stockings; then turned with a jerk,

And laying his finger aside of his nose,

And giving a nod, up the chimney he rose…

Notice, though, that whereas Irving’s St. Nicholas seems to be using that finger to glower at Van Kortlandt about founding a city, Moore’s St. Nicholas is using some kind of magical rising-up-the-chimney nose-finger device. Irving’s St. Nicholas is the imposing, adult, mythological St. Nicholas; Moore’s St. Nicholas is the child-oriented, magical, miniature St. Nicholas. Where the Romans had their household gods, the lares and penates; where the British had pixies and the Swedes had tomtes, the Americans had St. Nicholas. Like the other supernatural beings, his ultimate home was in the unreachable wilderness; but like the little household sprites, he’s also a domestic character, coming all the way into the home — no longer throwing things in through the window or down the chimney, no more intimidating than a “pedlar just opening his pack.”

So how did St. Nicholas — or Santa Claus, as he had come to be known — get big again? It seems to have happened in the early years of the twentieth century, which is just when memories of the sprites and pixies and all the little folk were fading. Brownies were popular in the 1920s (and had a baked good named after them!), but then they too faded from memory. And adults were impersonating Santa, and adults were adult-sized. So we not only lost the idea of Santa as a miniature being, but we lost the idea of all miniature beings as our domestic companions. Santa is the only one of that great legion of miniature domestic beings to have survived modern America, almost as if he really did come across the Atlantic as the figurehead of the Goede Vrouw. And even if we’ve forgotten how small he’s suposed to be, we still leave him milk, just as we used to do for so many other little folk, as a token of our thanks.

_______________________________________________________________

Here is the original version of “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” partially transcribed from a manuscript written out by Clement Clarke Moore in 1862. This preserves the original wording, which is often changed in modern printings, such as “…ere he drove out of sight” (where modern editions usually have “…as he drove…”) and “Happy Christmas” instead of “Merry Christmas.”

‘Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there;

The children were nestled all snug in their beds;

While visions of sugar-plums danced in their heads;

And Mamma in her ‘kerchief, and I in my cap,

Had just settled our brains for a long winter’s nap,

When out on the lawn there arose such a clatter,

I sprang from the bed to see what was the matter.

Away to the window I flew like a flash,

Tore open the shutters and threw up the sash.

The moon, on the breast of the new-fallen snow,

Gave the lustre of midday to objects below,

When, what to my wondering eyes should appear,

But a miniature sleigh, and eight tiny rein-deer,

With a little old driver so lively and quick

I knew in a moment he must be St. Nick.

More rapid than eagles his coursers they came,

And he whistled, and shouted, and called them by name:

“Now, Dasher! now, Dancer! now Prancer and Vixen!

On, Comet! on, Cupid! on, Donder and Blitzen!

To the top of the porch! to the top of the wall!

Now dash away! dash away! dash away all!”

As leaves that before the wild hurricane fly,

When they meet with an obstacle, mount to the sky;

So up to the housetop the coursers they flew

With the sleigh full of toys, and St. Nicholas too—

And then, in a twinkling, I heard on the roof

The prancing and pawing of each little hoof.

As I drew in my head, and was turning around,

Down the chimney St. Nicholas came with a bound.

He was dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot,

And his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot;

A bundle of toys he had flung on his back,

And he looked like a pedlar just opening his pack.

His eyes—how they twinkled! his dimples, how merry!

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry!

His droll little mouth was drawn up like a bow,

And the beard on his chin was as white as the snow;

The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth,

And the smoke, it encircled his head like a wreath;

He had a broad face and a little round belly

That shook when he laughed, like a bowl full of jelly.

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf,

And I laughed when I saw him, in spite of myself;

A wink of his eye and a twist of his head

Soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread;

He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work,

And filled all the stockings; then turned with a jerk,

And laying his finger aside of his nose,

And giving a nod, up the chimney he rose;

He sprang to his sleigh, to his team gave a whistle,

And away they all flew like the down of a thistle.

But I heard him exclaim, ere he drove out of sight—

“Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good night!”